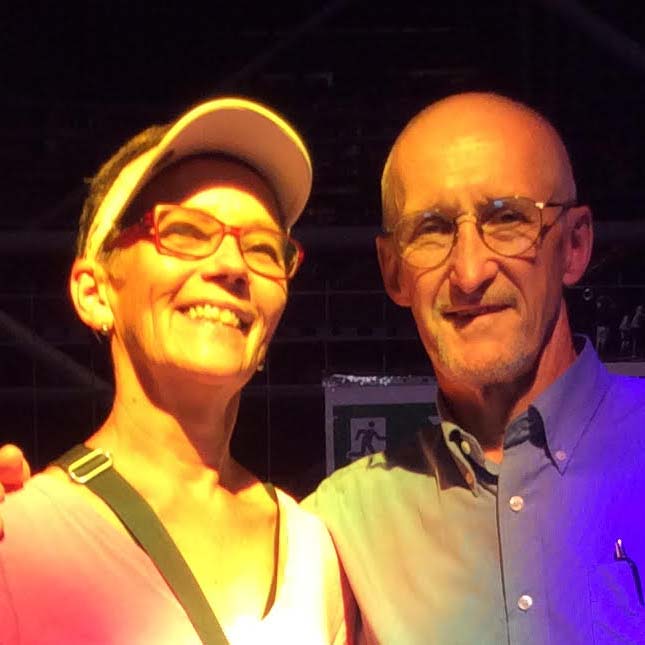

By Margaret Jensen

We are high up above the Hat Creek Valley, in the Lassen National Forest, at about 4,000 feet. Henry Giacomini has just summed up his entire summer’s work: “We chase grass!” There is a Black Angus Hat Creek Ranch cow standing in partial shade, with a long piece of dry grass hanging from her mouth. She is not chewing the grass, and she is barely tracking our passing truck with her eyes. She seems awake, but deeply at rest. For just a minute, watching this cow, it is possible to imagine that raising grass-fed beef is a simple process, a simple way to earn a living. Then, whoosh, that moment is past, as Henry begins talking about all the reporting required by the U.S. Forest Service in exchange for the grazing permits on this section of forest, then interrupts himself to point out the sign for the Pacific Crest Trail, then is interrupted by his wife, Pam, as she spots some cattle who lagged behind during yesterday’s cattle drive.

We are high up above the Hat Creek Valley, in the Lassen National Forest, at about 4,000 feet. Henry Giacomini has just summed up his entire summer’s work: “We chase grass!” There is a Black Angus Hat Creek Ranch cow standing in partial shade, with a long piece of dry grass hanging from her mouth. She is not chewing the grass, and she is barely tracking our passing truck with her eyes. She seems awake, but deeply at rest. For just a minute, watching this cow, it is possible to imagine that raising grass-fed beef is a simple process, a simple way to earn a living. Then, whoosh, that moment is past, as Henry begins talking about all the reporting required by the U.S. Forest Service in exchange for the grazing permits on this section of forest, then interrupts himself to point out the sign for the Pacific Crest Trail, then is interrupted by his wife, Pam, as she spots some cattle who lagged behind during yesterday’s cattle drive. As it turns out, “grass-fed” cattle raised by Hat Creek Ranch include those who spend their summers foraging amidst pines and scrub, returning to a few stock ponds to drink water, and following the grass ever higher as the last snows melt. In the truck with the Giacominis, we move at only about ten miles per hour on a dirt road, but mid-way through the afternoon, it feels like we’ve been spinning around in a whirlwind of activity and information. That black cow is like the one object in a tornado that’s left standing after everything around it has been leveled. The cow is recognizable, a constant. Everything else in this story is about change, uncertainty, complexity, and hard work. I’ve eaten Hat Creek Grown grass-fed beef and loved it, but there’s a lot more to the story of my hamburger than I expected. It keeps coming back to the grass.

As it turns out, “grass-fed” cattle raised by Hat Creek Ranch include those who spend their summers foraging amidst pines and scrub, returning to a few stock ponds to drink water, and following the grass ever higher as the last snows melt. In the truck with the Giacominis, we move at only about ten miles per hour on a dirt road, but mid-way through the afternoon, it feels like we’ve been spinning around in a whirlwind of activity and information. That black cow is like the one object in a tornado that’s left standing after everything around it has been leveled. The cow is recognizable, a constant. Everything else in this story is about change, uncertainty, complexity, and hard work. I’ve eaten Hat Creek Grown grass-fed beef and loved it, but there’s a lot more to the story of my hamburger than I expected. It keeps coming back to the grass.

The day before, in what must have looked like a scene from a western movie, Pam and Henry and their ranch hands herded about 450 cows and their calves up the mountains on horseback. The cows and calves might now startle hikers and hang-gliders who take this road past the Hat Creek Observatory and up the Murken Bench. It is impossibly scenic and timeless to a non-rancher, but the Giacominis are most interested in pointing out how lush the forage is, a benefit from the late, wet spring that caused Sacramento Valley farmers all kinds of problems. “Somebody is always benefitting from the weather, somewhere,” Henry says, “but it usually isn’t us!” We stop and look back down to the green checkerboard meadows far below, where the rest of the Ranch’s herds are small black dots in the late afternoon sun.

The day before, in what must have looked like a scene from a western movie, Pam and Henry and their ranch hands herded about 450 cows and their calves up the mountains on horseback. The cows and calves might now startle hikers and hang-gliders who take this road past the Hat Creek Observatory and up the Murken Bench. It is impossibly scenic and timeless to a non-rancher, but the Giacominis are most interested in pointing out how lush the forage is, a benefit from the late, wet spring that caused Sacramento Valley farmers all kinds of problems. “Somebody is always benefitting from the weather, somewhere,” Henry says, “but it usually isn’t us!” We stop and look back down to the green checkerboard meadows far below, where the rest of the Ranch’s herds are small black dots in the late afternoon sun.

“Hat Creek Grown” is the label on the Giacomini’s packages, but the ranch’s sign has a historic title, “Hat Creek Hereford Ranch,” visible along Highway 89 to travelers heading north from Lassen National Park or south from Burney or Fall River. The ranch has been in Pam’s family since 1903, and over the decades, her entrepreneurial father addressed the boom-and-bust cycles of cattle ranching by adding a campground and a small hydro power plant on the property. The Giacominis’ house and many of their outbuildings sit just a few yards from Hat Creek, home to world-class trout fishing. The setting—in the middle of tall pines, with acres of deep green pasture spreading out behind and to the sides, and mountains framing the view to the east—is as beautiful as it gets in the mountains of northeastern California. Add ranchers on horseback gently moving cattle from one green pasture to the next, and ”bucolic” just doesn’t cover it.

The Giacominis’ path to producing grass-fed beef under their own label has been anything but straight, and along the way, they’ve found multiple motivations to arrive at their current business model. Moving from Ferndale in 1988 to take over the ranch’s cattle operation, they raised cattle for other labels, including the well-known Niman Ranch, for many years. They followed the conventional practice of switching from pasture to grain-finishing the animals for the final months (think “corn-fed”). Their costs varied widely depending on the availability of grain and the concurrent costs for transportation of grain to cattle or vice-versa, and they were at the mercy of their wholesalers’ demands. Meanwhile, they were attending industry conferences where people talked about “niche marketing” of specialty beef (specialties like “all-natural,” “organic,” “grass-fed,” etc.) directly to customers, but almost no one was doing it. Pam and Henry gradually concluded that all the “disconnects” in corporate agriculture were proving harmful to the long-term survival of small family farms like theirs and to customers as well.

The Giacominis’ path to producing grass-fed beef under their own label has been anything but straight, and along the way, they’ve found multiple motivations to arrive at their current business model. Moving from Ferndale in 1988 to take over the ranch’s cattle operation, they raised cattle for other labels, including the well-known Niman Ranch, for many years. They followed the conventional practice of switching from pasture to grain-finishing the animals for the final months (think “corn-fed”). Their costs varied widely depending on the availability of grain and the concurrent costs for transportation of grain to cattle or vice-versa, and they were at the mercy of their wholesalers’ demands. Meanwhile, they were attending industry conferences where people talked about “niche marketing” of specialty beef (specialties like “all-natural,” “organic,” “grass-fed,” etc.) directly to customers, but almost no one was doing it. Pam and Henry gradually concluded that all the “disconnects” in corporate agriculture were proving harmful to the long-term survival of small family farms like theirs and to customers as well.

The Giacominis already had years of experience of direct marketing another ranch product, hay, to individual customers, primarily in the Redding and Cottonwood areas.

The Giacominis already had years of experience of direct marketing another ranch product, hay, to individual customers, primarily in the Redding and Cottonwood areas.

Banking on their own experience and a sense that, while they might not make any more money, they might at least have more control, they decided to start their own meat label in 2003, still using the grain-finished model. At that time, “grassfed” beef had the reputation of not tasting nearly as good as grain-fed beef and, rather, of being lean and too tough. But Henry began paying close attention to the genetics of their cattle, and in 2006-7 was seriously experimenting with grass-finishing some of their herd. They got a lot of local feedback through an unusual local partnership when they ran a special sale to customers of the busy Les Schwab Tire store in nearby Burney. By 2008, they felt they knew what “really good grass-fed beef” should taste like, and after grain prices spiked very high, they sold their last grain-finished cow that winter.

The genetics of a cow that will produce great tasting meat on a strictly grass diet are not, according to Henry, beyond what is already readily available to many ranchers. The Giacominis’ earlier switch from Herefords to Angus in the 1980s had put them much closer to the ideal. The cattle that do best on grass need to have moderate-sized frames and also build internal stores of fat around muscle, the “marbling.” The heifers need to be able to produce milk while still keeping some fat on their backs. Pam adds, “And they should have an easy temperament too, since they get moved a lot.”

Once selective breeding had solved the flavor problem, the Giacominis’ challenges shifted from producing great-tasting meat to two other areas: marketing enough of that meat at prices that will allow Hat Creek Grown to stay in business, and then making sure there’s always enough grass to produce that meat!

“In grass, the carbs are higher up and the proteins are lower—for finishing cattle, we want them eating all those carbs,” Henry says.

Explaining to a non-rancher which animals are on which grass, why, and how long they’ll be there can be complicated, but Pam does her best. The cows in the lush pastures are the ones that are being “finished” for two to six months before becoming steaks, while the breeding herd is up in the mountains. And “grass” is not just, well, grass.

As we drive quickly past the creek-watered meadows, it all just looks green. But stand in the corner of one meadow as the cows clomp by on their way to a newly-opened area, and it’s easy to see that the “grass” is a mixture of many things, some of which the cows munch down more deeply than others. Pam points out clover, alfalfa, orchard grass, bluegrass, some native plants, “and other things that just show up.” The herds that eat this grass are moved every couple of days so that each section can easily regrow.

As we drive quickly past the creek-watered meadows, it all just looks green. But stand in the corner of one meadow as the cows clomp by on their way to a newly-opened area, and it’s easy to see that the “grass” is a mixture of many things, some of which the cows munch down more deeply than others. Pam points out clover, alfalfa, orchard grass, bluegrass, some native plants, “and other things that just show up.” The herds that eat this grass are moved every couple of days so that each section can easily regrow.

Rotation patterns are based on a system that—as Henry and Pam describe—takes into account the weather, possible alternative uses of certain meadows for hay crops, the availability of someone to reposition electric fencing or mend gates, and then the need to fit these fence tasks into the schedule of a zillion other tasks!

“Rotation is about building soil fertility, too,” Henry explains. The right amount of cow manure replenishes the soil; too much can build up to amounts that might pollute irrigation run-off. He notes that among other reasons why he’d like to get out of the hay business (“Argh, machinery replacement costs!”), haying doesn’t contribute to soil fertility the way that careful herd management does.

To complicate the grazing process, some herds are on neighbors’ meadows not contiguous with their ranch, and a few herds are being “finished” for other ranchers who also want to produce and market grass-fed beef and who have recognized the Giacominis’ expertise. These cattle may be moved in or out on various schedules. Finally, Hat Creek cannot produce grass all year, so in the late fall “when the rains come,” the herd is moved from the high range and transported down to a 10,000 acre leased ranch in Oak Run, where calves are weaned and the herd graze all winter until they return in May.

Trying to grasp it all, I find myself imagining a Rubik’s cube where the composite small cubes are cows, grass, water, cows in transit, customers, and then maintenance/repairs. Henry moves the pieces every day, trying to align the cubes just once before dusk, if he’s lucky. Phew!

The Giacominis must be doing something right in carefully managing the range. In 2010, after working with Lassen National Forest officials and the U.C. Cooperative Extension to design and implement an ambitious watershed management process, they received an award from the Society of Range Management, a professional organization that supports the sustainable use of rangelands. Pam explains that grazing plans required for their federal allotments are so rigorous that “taxpayers really don’t have to worry that public grazing land is being mismanaged now.”

In winter, the ranch frequently sits under snow, and the Giacominis work inside on the second big challenge, marketing their product well enough to make a living. While their Hat Creek location enables the Giacominis to raise wonderful cattle, it’s the worldwide web and associated technology that is allowing them to be profitable as such a small operation.

Technology comes into play in interesting ways. Just before my visit, they had wrapped up a sale of steer calves through a video auction. Because of such video sales, potential buyers do not have to travel to remote locations, and the Giacominis do not have to transport cattle to stockyard auctions. Also, like

other niche marketers, they have found Internet sales to be a great way to reach customers who appreciate their product and are willing to pay an adequate price. They have teamed up with the Lazy 69 Ranch in Round Mountain to do joint web marketing, and in fact, all the beef now sold under the Lazy 69 name is being raised by the Giacominis.

I’m visiting on a Sunday, usually the day all orders are prepared for shipping, so Henry and Pam show off their well-organized walk-in freezer and the shipping shed, where sit pallets full of different-sized foam shipping containers. Pam notes that it took them a while to find containers that would really do the job of keeping meat frozen as it traveled across the country. “Other places can use dry ice, but for us, the nearest dry ice distributor is in Redding, a hundred miles away.”

Having control over their product means they can work with small stores in the region to provide just the right amount of inventory and customized marketing materials. I had driven past such an example of this in Burney—a perfectly-sized “Hat Creek Grown” sign in the window of the new Hearthstone Health Foods store on Main Street. They would love to sell all their product locally, but they’re too small to be in the chain groceries and too big for regional specialty stores only, so at least, as Henry says, they can interact directly with customers, even if they’re in Texas or L.A. They do provide meat to several restaurants in Hat Creek, Mount Shasta, and Redding, and to the Country Organics store in Redding.

I ask the same question that the Giacominis hear frequently: why haven’t they pursued organic certification? They have some disagreements with the ways that the organic regulations have been written for the beef industry, believing that what makes sense to address problems in giant, feedlot-based organic operations doesn’t necessarily fit with their model; they also believe organic certification costs are too high, and, as Pam wrote for their website, “Our cattle are beyond organic, they are extreme natural. Our beef never receive any type of hormone, growth promotant, or unnecessary antibiotic. The grass they graze is completely natural. We invite any customer to come a take a look at what we are doing with our land and our cattle. Henry and I stopped any fossil fuel or chemical use on our home ranch in 2002. The ranches we lease are either native ranges or the owners agree with our philosophy and let us manage their property with the same ethic of no fossil fuel inputs.”

We good-naturedly debate some of the pros and cons of organic certification, and bemoan some of the economic issues common to both small ranches and small farms, and suddenly it’s dusk. We’re on the other side of the ranch from the freezer, so I leave without buying the meat I intended to take home, but that’s OK. I already have some, and I know how succulent and delicious it will taste. I’m a satisfied customer, the end point on a cattle trail that began in Hat Creek in 1903, wanders all over some of the best range and pasture in northeastern California, and passes by that black heifer up in the mountains, contentedly standing in the shade, good grass hanging from her mouth.