Fruits, Veggies, & Bee Hotels

Back in 2006, some students asked Chico State University professor Lee Altier why the campus farm didn’t grow vegetables for the campus community. His response? “That’s a great question. I think we should start.”

The university was willing, and the result is the Organic Vegetable Project (OVP), which harvested its first crops in spring, 2008. The OVP consists of 10 acres of land adjacent to the 800-acre university farm. Grants from the university, the Earl Foor Foundation, and others got the project launched, initially with one acre in production and currently with three of the ten available acres in use. Unlike the university farm, which relies mostly on conventional farming methods, the OVP is certified organic and incorporates permaculture techniques.

Altier, a professor of agriculture, has an ambitious vision for the OVP. “When we wrote up the mission statement, I said it needs to be a community asset. We need to think about this in a broader educational sense for all the people who want to learn more about their food supply and how to grow food.”

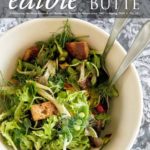

For starters, the OVP is a splendid example of how to grow food. A walk-through in midsummer reveals rows of thriving zucchini, lettuce, peppers, melons, tomatoes, eggplant, berries, and grapes. “We’re bringing more vegetable diversity to produce at the farm,” says OVP Director Jamal Javanmardi, who replaced Professor Altier in this role in 2019. Javanmardi has introduced Persian melons, tarre Irani (a flat-leafed herb related to chives), Iranian basil, and Asian vegetables like mizuna from his native Iran. In total, he says, they grow about fifty varieties of fruits and veggies and deliver approximately 10,000 pounds of produce annually. In addition, Javanmardi recently started growing organic mushrooms.

STUDENTS ON THE FARM

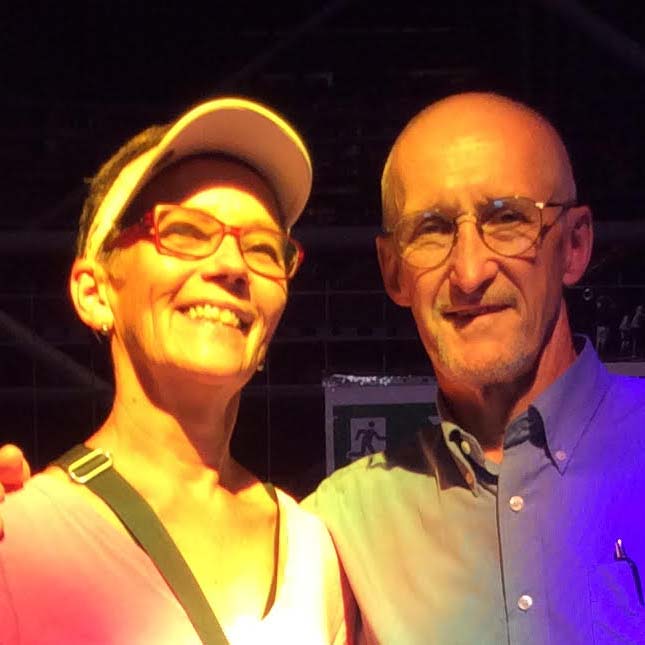

Day to day, Project Coordinator Scott Grist manages OVP operations with the help of students working as paid staff, interns, or to fulfill class requirements. “The most important things we do here are expose students to local, organic produce on campus and educate young ag students at the farm about sustainable agriculture practices,” says Grist, who welcomes 40–50 students per year to the farm. “It’s a great learning experience and a chance to see organic production take place,” says student Alexis Paez, who is pursuing a degree in plant and soil science. Recent graduate Brianne Shannon worked at the OVP for over a year, first as part of her plant science class and then as an employee. “I was able to have a hand in every aspect of the process, from seeding and transplanting into the fields, to weeding, harvesting, processing, and even selling our produce,” says Shannon, who is now a student teacher with a degree in agriculture education.

Students run a weekly farm stand where community members can purchase fresh produce. And students help prepare weekly CSA (Community Supported Agriculture) boxes for local residents. Each week in April through November, CSA members get seven or eight different types of produce for a cost of $100 per month. Currently, twenty families are taking part, and there’s typically a waitlist. Shannon says that seeing the CSA members each week and telling them about the goodies in their box was a favorite activity for her. She also enjoyed finding out about vegetables she hadn’t known previously, like zucchini and kohlrabi, and then enriching her diet by making “zoodles” (zucchini noodles) and other new dishes.

Graduate Edgar Castrejón, who worked at the OVP for nearly two years, also experimented with new ways to prepare the veggies he helped to grow and harvest. Castrejón shared his ideas on social media and added written recipes to the CSA boxes, like Pickled Candy Cane Beets with Daikon. Castrejón expanded upon these recipes in his recently published book, Provecho: 100 Vegan Mexican Recipes to Celebrate Culture and Community. “The OVP opened so many doors for me,” he says. ‘I’m Here for the Vegetables’

On Monday mornings, OVP students deliver produce to the on-campus Hungry Wildcat Food Pantry, which provides fresh and packaged foods at no cost. The pantry is run by Joe Picard, the Chico State basic needs administrator, who established a connection between the OVP and the pantry back in 2013. Picard created one-dollar vouchers called “veggie bucks,” which he funded by putting $20 from his own wallet into a donation jar at the OVP. More donations were gradually added, and students started spending their vouchers on organic produce.

Today, the pantry is funded by a wide variety of grants and donations, and those purchase about eight tons of OVP produce annually. “Come Monday morning, the students are here,” says Picard. “They say, ‘I’m here for the vegetables.’”

Picard encourages students to expand their palates and experience top-quality food. “We want the highest nutritional value and the best produce available for those most in need,” he says. “We don’t take the food for granted; it’s really special and we learn. When he [Scott Grist] brings the Romanesco, it’s ‘Oh my gosh, what’s this?’ When students ask, ‘What do you with that?’ I say, ‘It’s like a cauliflower, look it up.’”

Although Picard wishes the pantry could be for emergencies only, it’s a bustling place. He says that 50% of CSU Chico students are food insecure and that the pantry served over 5,000 students last year. On a typical busy day, 150–200 students come in to supplement their meals. Through the Basic Needs department, Picard promotes longer-term security by helping students sign up for CalFresh benefits and developing resources that connect students to stable housing and employment.

In addition to supplying the food pantry, the OVP sells its produce to campus dining rooms, providing an ongoing supply of organic fruits and veggies for campus meals. Some specialty items, such as shishito and Jimmy Nardello peppers, are also sold to local restaurants.

Certified organic by California Certified Organic Farmers (CCOF), the OVP is part of the university’s Center for Regenerative Agriculture. But because the OVP is bordered closely on one side by a walnut orchard that’s part of the non-organic campus farm, there’s the risk that pesticides sprayed on the walnuts could blow onto the OVP’s organic vegetables. To prevent this, Grist planted a barrier crop of elderberry bushes that he doesn’t harvest along the edge bordered by the walnut orchard; the shrubs act as a protective barrier for the OVP’s plants and soil.

THE FISH AND THE BEES

Beyond growing produce on the land, the OVP ventured into aquaponics several years ago, when a grant allowed some engineering students to build an aquaponics system for their senior project. “It’s a closed system of production,” says Altier. “You have fish that eat their food and they poop into the water, which fertilizes the water for the plants; the plants extract the nutrients and clean the water, removing the ammonium and nitrates, and it goes back to the fish tanks.” Altier takes groups of students to Thailand and Nepal for study-abroad summer programs, and it was in Nepal that they toured an aquaponics facility almost entirely dedicated to organic strawberries. He was so impressed with the quality of the strawberries, which were grown year-round, that he transplanted this idea back to the OVP. Altier notes that aquaponics systems are highly water efficient, using far less water than crops in the field.

Insects are also doing their part at the OVP, where a hedge row with native and other year-round flowering plants surrounds the field to attract pollinators. There’s also a “bee hotel,” a big arch full of pieces of wood with holes drilled in them to attract native bees. These hotels are designed for native cavity-dwelling solitary bees (unlike honey bees), which look for crevices where they can lay their eggs. “It’s low maintenance and great for our crops,” says Altier.

The hotels were a big hit at a popular OVP workshop, where community members constructed their own bee hotels. Grant funding from the California Department of Food and Agriculture supports the workshops, which have also focused on soil health, crop rotation, and management of beneficial insects. With this funding, the OVP has reached out to underserved communities, created community gardens in and around Chico, and promoted CalFresh membership so more people can afford fresh produce.

Research is also a high priority at the OVP. The project runs variety trials of tomatoes, lettuce, melons, kohlrabi, peppers, and other produce grown to assess taste, productivity, and issues with pests. Information on the most promising varieties is then shared with local growers. Another area of research is finding ways to reduce tillage when growing vegetables. By planting without disturbing the soil, the goal is to increase organic buildup and water retention and to keep more carbon in the ground. Possibilities for the OVP seem endless. “The sky’s the limit in terms of value-added projects and new activities,” says Altier, who continues to use the OVP for his classes. “It’s pretty amazing, all the things you can do with three acres.” 1

- For more information and to sign up for the CSA in 2023, visit csuchico.edu/ag/university-farm/ovp.shtml and csucag.wixsite.com/chicostateovp

Rachel Trachten writes about local food in connection to social justice, education, business, and the environment. View her stories at racheltrachten.contently.com.