The rice and duck harvests are in, the community dinner “Duck Five Ways” has been held, and we now take time to reflect on the past and look towards the future. Our family risked so much during their journey from the Azores to California. We Lopes feel a deep connection with our family who set out into the unknown in hopes of a better future. That spirit of determination, exploration, and perseverance echoes in our new venture as duck rice farmers and inspires future extensions of all we have learned.

THE ELDER LOPES REFLECTS

Grandpa John Sylvester Lopes left the island of Sao Jorge in the Azores in 1899 with the clothes on his back, two loaves of bread, very little money, and no English-speaking skills. He disembarked the ship at the Statue of Liberty and worked until he earned enough money to travel many months by wagon to the foothills of Winnemucca, Nevada. There, he raised sheep and met my grandma, also an immigrant, who happened to be from Sao Jorge as well. My dad was born there in 1904.

Grandpa John Sylvester Lopes left the island of Sao Jorge in the Azores in 1899 with the clothes on his back, two loaves of bread, very little money, and no English-speaking skills.

Grandpa’s sheep were being stolen by the big ranchers around him. He went to court and won the lawsuit, but the judge turned to him and said: “You may have won the lawsuit, but these big farmers aren’t going away and they’re looking for trouble! May I suggest you leave Winnemucca soon? This is no place to raise a two-year old.” So Grandpa and Grandma journeyed across Donner Summit, eventually arriving at the Point Reyes peninsula, where my grandma had relatives, and working until Grandpa saved enough to guide their little sheep herder shack across California and find a cozy little spot in a small community called Codora, near Princeton.

I was blessed with grandparents who enjoyed a simple life of hard work. They built a rice farm from the ground up, a big change from sheep herding. But they succeeded, and I’m able to carry on the tradition that they worked so hard for. When my dad reached 78 years of age, I would help him up the steps of our farm machinery so he could perform his duties. Once up and sitting in the driver’s chair open to the world, he grew a smile that filled his face. This gave me pleasure, knowing he was happy in his last days.

I spent the first years of my farming career driving a two-ton bobtail truck from the field to the rice dryers. From there I moved to the bankout wagon, where I found most of the farming done. The harvester driver must concentrate continuously on what he’s doing or things could break real easily! My job was quality control, making sure the rice was being processed without breaking. I was like a monkey swinging in a tree. I would be on top of the harvester looking at the rice straw as it was being thrashed, making sure no rice was escaping! Then I’d swing over to the grain bin, where I would get a handful of clean rice and count the broken kernels. If I had more than three broken kernels, I had too many! I would jump to the ground and scan for escaped rice. If too many kernels were broken or escaping, I gave the broken signal sign to my brother, and he would make the necessary adjustments. The difference in high quality rice (whole kernel! opalescent color!) would pay for our gas, diesel, and wages for our employees and an after-harvest dinner party, woohoo!

As times kept getting tougher, with costs going up and the price of rice staying the same or lower, I was able to maintain the farm so my parents had enough money to live on and keep the farm going. My mother, Rose, raised us comfortably: good food always and one clean set of clothes for Sunday. My parents taught us to give when you can, help when you can, always leave people feeling better than when they arrived!

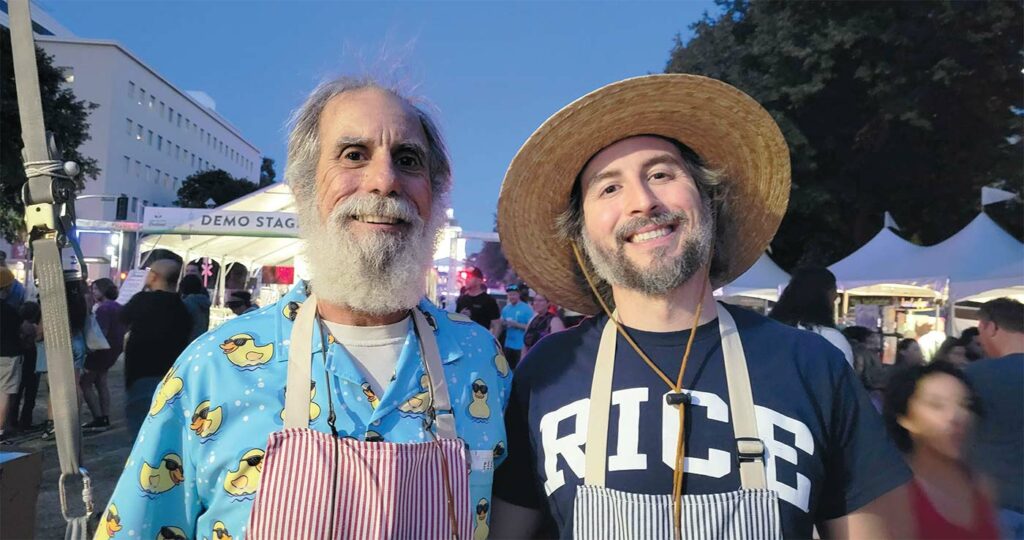

Our story now is really about my son Christopher. My son, he’s the one I take my hat off to; he has his own path, and he accelerates people around him. Never in my wildest dreams would I imagine hosting dinners selling my rice and my ducks, my gosh, everything turning out so beautifully. “It’s in the heart of giving that you succeed in life.” And I do believe that lesson has been learned by my son. He’s my manager in our new family business, Lopes Family Farms! He is my vision into the future.

My mother, Rose, raised us comfortably: good food always and one clean set of clothes for Sunday. My parents taught us to give when you can, help when you can, always leave people feeling better than when they arrived!

WHEN DUCK RICE MEETS POPULAR SCIENCE

From the beginning my dad and I would often let our imaginations run wild with how the duck rice farming method would change our lives and impact the community, the rice industry, and even the world. We envisioned the adoption of duck rice farming throughout the California rice fields, with its concurrent reduction of water use in this state that so needs to reduce.

To grow California’s half million acres of rice as duck rice, we’d need 500 million trays for starting the plants and 50 million ducks each year. The enormous number of trays, ducks—and the specialized equipment to implement the duck rice method—mean duck rice farming will not scale up fast. We soon saw a different vision to greatly reduce water usage, when we met Brian and his father Scott Park, innovative organic farmers in Meridian, California. The Parks’ way of planting rice was a way born of necessity when their young rice crop grew tall too quickly and strong winds uprooted the entire crop. They needed to replant using the equipment they had on hand.

They drained their fields and let them dry out until the topsoil could support the weight of their equipment. Turning over the first inch of soil dislodged the young weeds there. That done, they rolled the field to compress the top couple inches of soil and trap moisture in the ground. After the moisture had time to even out in the soil, they used a drill seeder to plant rice, leaving six inches of spacing between rows. The moisture trapped in the ground germinated the seed, so they had no need for water until about a month later, when the rice starts were four to six inches tall and began to show stress.

Not only does this save the water usually used to flood fields and sprout rice seed. It also avoids the considerable damage the dreaded tadpole shrimp can wreak by eating rice taproots. And because they waited until the rice was several inches tall to flood the fields, the rice plants’ growth wasn’t slowed, as they are in conventional planting methods, by the scum that forms on the surface of the water. Instead, that scum hinders weed growth. Further, the mature rice doesn’t lodge, since it has more room to grow in the rows. (Read more fully about the Parks’ process on our website, lopesfarms.com.)

The water savings are considerable, as with our duck rice method. The big issue is managing weeds. While the Parks hire workers to hoe them, we think we have found another solution that might end up being cheaper and faster, depending on acreage farmed, but it’s futuristic and unproven in rice production…until next spring, that is.

Next spring, we’ll combine what we learned from Takao Furuno about the duck rice method, the drill seeding method devised by the Parks, and some futuristic tech developed by a company called Verdant Robotics. This innovative company uses AI machine vision and robotics to distinguish between rice and weeds in a field. It targets only the weeds with a stream of an organic certified herbicide called Suppress. Its active ingredients, capric acid and caprylic acid, occur naturally, in oils like coconut and palm oils. They dry out the leaves of the weeds, which can kill them or stunt their growth for a while. With less competition, the rice grows and we then flood the fields and release ducks so they can do what they do best, eat weeds and fertilize, for the rest of the growing season.

While we love ducks, they do add complexity that farmers may not want to manage. The six-row weeder we used this season can take the place of ducks and allow new and established organic farmers to manage weeds. Using the Parks’ drill seeding method, we won’t need rice trays and all the specialty equipment that the trays require to transplant rice from the rice mats to the field. Combining these methods could help transition all rice production in California to organic!

Next spring, we’ll combine what we learned from Takao Furuno about the duck rice method, the drill seeding method devised by the Parks, and some futuristic tech developed by a company called Verdant Robotics . . . . Combining these methods could help transition all rice production in California to organic!

THE AMERICAN CRAFT SAKE REVOLUTION BEGINS

Along our way, we learned that for all our dreaming, reality sometimes exceeds even the wildest dreams. In May of this year, Paul Browning, of Far West Rice, where we have our rice milled, informed us that he had a potential customer who wanted us to grow some specialty rice. That customer was Jake Myrick, the owner of Sequoia Sake, an award-winning artisan sake brewery in San Francisco. Myrick sought an organic rice farmer to grow a variety of sake rice called Omachi. It is the oldest variety of sake rice, dating back to 1859. Omachi is a pure strain, and around 60% of all sake rice varieties are descended from it.

This variety of rice takes the longest to mature of any we’d ever heard of—180 days! Since we were already halfway through May, that meant the crop wouldn’t be ready for harvest until November, when early rains could ruin the crop. Other variables also expanded the risk, but we all decided to take it. We received the call from Jake on a Wednesday, met him at Rice Researchers, Inc., on that Friday to get the seed, and had the Omachi trays started that next Monday—and the three-acre planting yielded ~5000 pounds/acre, success! The majority of sake produced in the USA uses Calrose rice, and this crop was the first certified organic sake rice grown and harvested in America! Using organic Omachi will allow sake brewers to develop new flavors and profiles not possible before.

OUR RICE GOES TO SCHOOL

When we first started, no one had ever heard of duck rice farming, and we had the amazing opportunity to share and educate people about it. As word spread, one day we received a call from Miguel Alvarez, who works for a statewide organization called Community Alliance with Family Farmers. Miguel arranged for us to host a field day and demonstrate the duck rice method.

Folks from the California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) attended. We showed them all the bells and whistles. We set up our dirt shaker in the corner, had our weeder/mudder next to it, baby ducks in a pen, and a rice plugger ready for a demo. Michael Whamond, who works for the CDFA’s farm to school division, was there. The division offers Farm to School grants to encourage California schools to purchase produce from local farms: districts can receive grant funding to pay a decent price for food from the farmers, and the farmers receive funds to make improvements on their farm so they can more reliably provide food to the schools. Children also benefit, because they learn about where their food comes from and enjoy fresher, much healthier food. (When school districts purchase commodity brown rice, they pay about three dollars for a fifty-pound bag. No way can this support a farm!)

Michael helped us get our rice into some local schools. He saw how motivated we were to offer field trips to our farm as well as do presentations at the schools about duck rice farming and regenerative practices. The CDFA’s Farm to School program sponsored us on a trip to attend its annual conference down south in October. We’re now in talks with some of the southern districts to provide brown rice to their schools so they can do more from-scratch, farm-to-school cooking.

Back home, exhausted and elated, we donated twenty ducks to a festive gala, “Duck Five Ways,” at the Arc Pavilion in Chico, menu created by Donna Garrison and cooked by chefs Alex Cilensek and Erik Petersen. We traded tie-dyed shirts and muddy jeans for newly tailored suits and were given the seats of honor; then we presented a slideshow of our regenerative duck rice operation, and both my father and I gave speeches. The event brought in over ten thousand dollars for Butte County Local Food Network and Butte Environmental Council. Guests asked how to purchase our ducks for their own kitchens. We can’t thank the community enough for the show of support.

We traded tie-dyed shirts and muddy jeans for newly tailored suits and were given the seats of honor; then we presented a slideshow of our regenerative duck rice operation, and both my father and I gave speeches.

ALL TOGETHER NOW

Like our immigrant forebearers, we have taken big risks for our dream of a better life. Countless people we’ve come across on our route have helped, many of whom we’ve thanked in our previous three articles, but there are more to thank. We’d like to thank Rosemary Febbo for reaching out to Ray Laager, Susan Tchudi, and Linda Watkins-Bennet, who supported us by helping get our farm’s name out to the community through their media platforms and everyone who volunteered. And on a more personal note, I’d like to thank my mom June Lopes for supporting me and instilling in me the resilience to overcome life’s most difficult challenges, my father for all of his hard work making our dream a reality, and Elizabet Olvera, who stands by me and keeps me unafraid.

Bruce and Christopher Lopes raise organic ducks and rice on their farm in Princeton, which has been in the family for 113 years. This is the first in a four-part series and introduces readers to the family farm and its latest innovation, ducks ‘n’ rice. The Lopes’ ducks are featured on the menu of Grana and The Winchester Goose in Chico. Once milled this spring, their rice will join the ducks on Grana’s menu.